In the mid-1990s, Apple was in a rough place. The company had lost ground to Microsoft and struggled to compete with the growing wave of lower-priced PC clones. Windows machines were cheaper, more compatible with popular software, and quickly became standard. Inside Apple, leadership turnover and shifting strategies made it hard to build momentum.

As the company looked for new ways forward, it started branching out, experimenting with digital cameras, PDAs, and even releasing a television. Most of those projects didn’t last, but one stands out for how strange and ambitious it was: the Apple Bandai Pippin.

It was meant to be part game console, part low-cost Mac, and part internet device — an early attempt at blending computing and entertainment in the living room. Ultimately, it couldn’t compete with the generation of consoles that gave us the PlayStation and N64 classics. Fewer than 42,000 units were sold before it was discontinued, but it’s still one of the more interesting crossovers in Apple’s history and the world of 1990s gaming.

Related

9 generations of video game console media: from Magnavox PCBs to modern Blu-rays

The evolution of video game media across nine console generations, from circuit boards to Blu-rays and digital downloads.

Apple’s experimental years and the question of what comes next

Falling behind as Windows took the lead

Source: eBay

By the mid-1990s, Apple had lost its footing in the personal computing market. Windows 95 was the dominant operating system, and Macs had a harder time justifying their higher price. PC clones running Windows were cheaper, offered better hardware for the money, and had access to a rapidly expanding software library — an advantage Apple couldn’t match.

That price gap became known as the “Apple Tax,” and it wasn’t just perception — many entry-level and mid-range Macs offered less performance than their PC counterparts. Higher-end models held their own, especially in areas like graphics and multimedia, but they came at a premium. For most buyers, the Mac’s closed ecosystem and smaller software library made it feel like a niche option.

Leadership at Apple was also in flux. John Sculley was removed in 1993, followed by Michael Spindler, a quiet and behind-the-scenes executive who was replaced just three years later by Gil Amelio. Amelio’s brief tenure included major moves like the acquisition of NeXT, which brought Steve Jobs back into the company. It also coincided with a period of deep financial losses and internal uncertainty. At one point, Apple even explored the idea of selling itself — conversations were held with companies like IBM and Sun, but none led to a deal.

Looking beyond the Mac computers

Source: Flickr – Htomari

With its core business under pressure, Apple started looking for new revenue streams outside traditional computing. The company launched a string of experimental products, many of which tried to reimagine how people interacted with technology. Some of them were genuinely ahead of their time, like the Newton MessagePad, which helped coin the term “PDA,” and the QuickTake, one of the first consumer digital cameras. It featured handwriting recognition, mobile syncing, and a forward-looking interface, though its accuracy issues made it a target for jokes in pop culture.

Other products didn’t land quite as well. The Apple Interactive Television Box was part of a short-lived pilot program with telecom companies like Bell Atlantic and Time Warner, aimed at delivering digital content to televisions, well before streaming became mainstream. There was also the Mac TV, a hybrid Macintosh with a built-in TV tuner, which quietly came and went after a limited production run of around 10,000 units.

The Pippin came out of this same era of experimentation. It was Apple’s attempt to tap into the growing world of multimedia computing, where CD-ROMs, educational software, and early internet tools were starting to reshape the idea of what a home computer — or a game console — could be. Apple hoped that by combining gaming, education, and connectivity elements, the Pippin might find a space between a console and a low-cost Mac.

Why Apple decided to enter the game

Gaming was exploding in the mid-’90s

Source: eBay

The video game industry was changing fast in the mid-1990s. Sony had just launched the PlayStation in 1994, following a failed partnership with Nintendo over the Super NES CD-ROM — better known today as the “Nintendo PlayStation,” a prototype console that never made it to market. Sony went solo and found massive success, bringing CD-based gaming and 3D graphics into the mainstream.

Nintendo was preparing to launch the Nintendo 64, pushing 3D gaming even further, while Sega was already in the market with the Saturn. CD-ROMs were becoming the standard for games, and the line between computers and entertainment devices was starting to blur. It was clear that gaming was no longer a niche — it was a rapidly growing, highly competitive industry.

Apple had mostly stayed out of that world. However, with multimedia computing on the rise and game consoles becoming more like general-purpose media devices, the company saw a new opportunity. Philips had tried something similar with the CD-i just a few years earlier and failed, but Apple pushed ahead anyway, betting it could build something that would appeal to both gamers and everyday computer users.

The Pippin was built to be open

Source: Wiki Commons – All About Apple Museum

Apple didn’t set out to build a traditional game console. The Pippin was designed as an open platform—part computer, part media player, part game system. The idea was that third-party companies could license the hardware, customize it, and build their own versions of the system, similar to how multiple manufacturers produced Windows PCs.

In theory, this gave the Pippin a major advantage over tightly controlled consoles like the PlayStation or Nintendo 64. It was a model that echoed what Philips had tried with the CD-i, which also licensed its hardware to companies like Magnavox and LG. But like the CD-i, the open-platform approach never really took off — only Bandai and Katz Media ever released licensed Pippin hardware.

Apple wasn’t alone in thinking a multimedia console could appeal to a broader audience, but the CD-i had already shown how difficult that proposition could be. Philips had made many of the same bets just a few years earlier and hadn’t paid off. Apple was taking a similar gamble, and the warning signs were already there.

Related

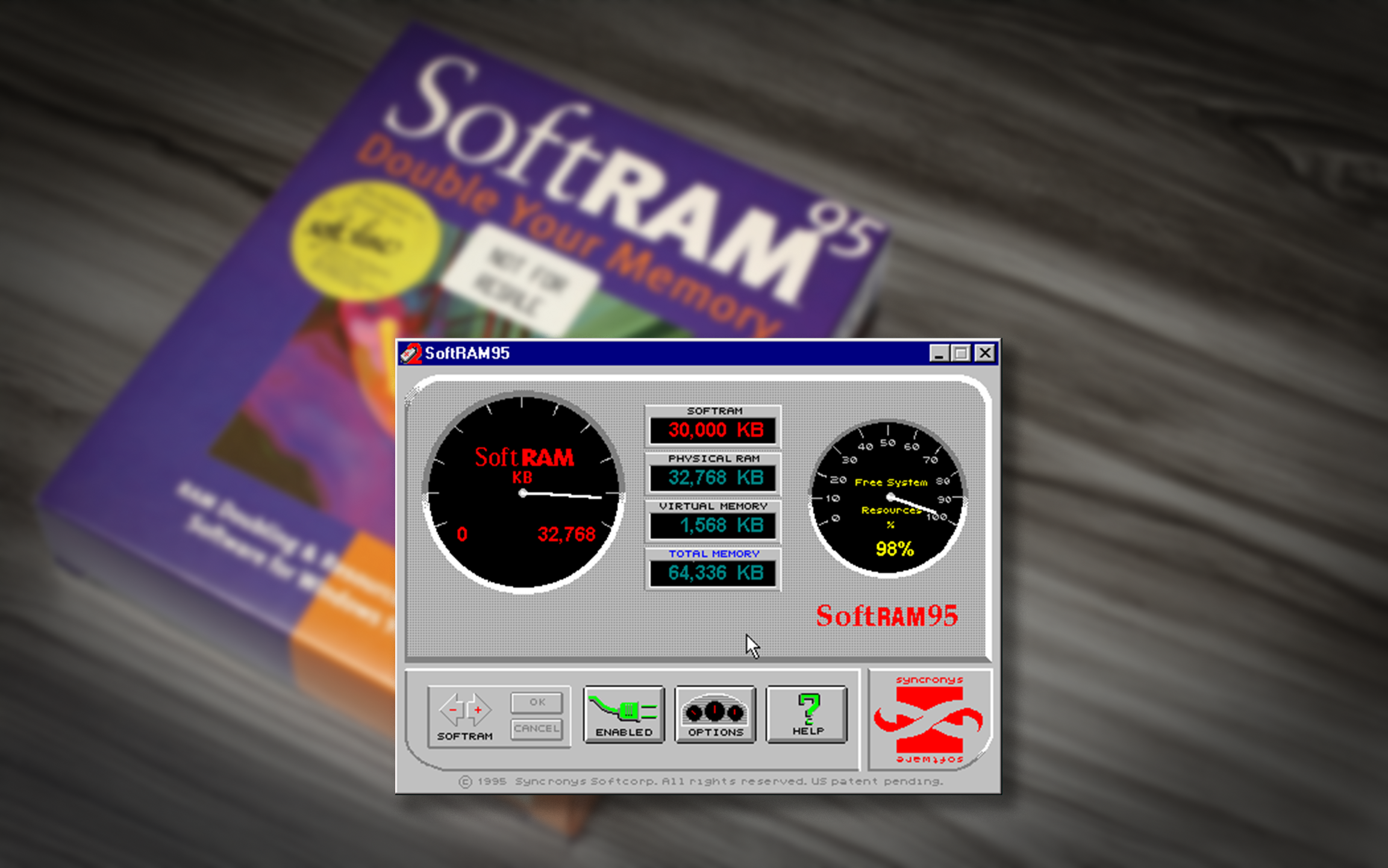

The great RAM doubler hoax of the 90s: How SoftRAM scammed over 650,000 PC users

Syncronys claimed it doubled your computer’s RAM—but it did absolutely nothing. Here’s the story behind one of the biggest tech scams of the 90s.

What Apple tried to build with the Pippin

Built on a stripped-down Mac

The Pippin wasn’t just a game console — it was built on a simplified version of macOS and used the same PowerPC 603e processor found in Apple’s lower-end computers at the time. It shipped with 8MB of RAM, a 4x CD-ROM drive, and composite video output for connecting to televisions. Apple’s idea was to create a device that could play games, run multimedia software, and serve as a low-cost personal computer.

In theory, it could do a lot: run certain Mac applications, browse the web, and offer a more open, flexible experience than traditional consoles. However, in practice, it was limited by its hardware and a lack of software support. It didn’t perform well enough to replace a proper Mac, and it couldn’t compete with dedicated consoles for gaming alone.

One of the Pippin’s more forward-looking features was its built-in 14.4 kbps modem.

Apple envisioned users browsing the web, downloading software, and maybe even playing online games—ideas that wouldn’t become common on consoles for several more years. But internet access in 1996 was still painfully slow. I was 14 at the time, and I remember setting songs to download overnight, never knowing if they’d finish or fail while I was asleep. The internet was also unreliable — sometimes just loading a single image in a browser could take minutes, revealing itself one line at a time, hardly the foundation for a connected gaming experience.

Why the Pippin couldn’t compete

Too expensive, too little to offer

Source: eBay

One of Pippin’s biggest problems was its price. At launch, it sold for $599 — about $1,200 today — making it nearly double the cost of a PlayStation ($299) and three times more than a Nintendo 64 ($199). For a device that didn’t have strong brand recognition in the gaming space, that price was a major barrier.

Worse, the Pippin didn’t have the software library to justify the cost. While Sony and Nintendo landed hits like Final Fantasy VII, Super Mario 64, and Resident Evil, the Pippin offered mostly educational titles and multimedia software. A few games showed promise — The Journeyman Project and Gundam 0079 among them — but nothing exclusive or compelling enough to drive hardware sales.

Apple and Bandai had hoped that developers would embrace the platform, but few were willing to take the risk. The small user base, uncertain future, and limited hardware all made the Pippin a tough sell. And since most of its games were also available on Windows PCs, there wasn’t much incentive to choose the Pippin over more affordable, better-supported options.

A product without a clear audience

Source: eBay

The Pippin’s other major flaw was that it didn’t know what it wanted to be. It was marketed as a game console, an educational device, and a home computer alternative—but it wasn’t particularly strong in any of those categories. It wasn’t powerful enough to compete with consoles and was too limited to function as a full-fledged computer.

This lack of focus made it difficult to market and even harder for consumers to understand. From a modern perspective, the problem seems obvious. However, in the mid-90s, when home computers were still expensive and new to many households, Apple may have believed there was room for a device that could straddle both worlds.

That hybrid approach might have made sense for someone who didn’t already own a computer and saw value in buying one that could also play games. However, in the mid-1990s, home computers were still relatively expensive and not yet widespread, so the audience was limited. Meanwhile, people shopping for a game console wanted something focused entirely on games. The Pippin sat in an awkward middle ground — too limited to be a real computer, and too unfocused to compete with dedicated gaming systems.

Related

Before they were famous: 5 early game console prototypes that shaped gaming

Five early console prototypes that influenced gaming history, from Sega’s handheld to the Nintendo PlayStation.

The Pippin’s place in Apple history

Source: Flickr – Jason Scott

Although the Pippin was a commercial failure, some of its ideas weren’t far off. Its focus on internet connectivity hinted at the future of online gaming, and its attempt to blend computing and entertainment anticipated the path that mobile devices and modern consoles would eventually take. In hindsight, it aimed at a market that hadn’t fully formed yet.

More importantly, the Pippin marked the end of an era for Apple. When Steve Jobs returned in 1997, he quickly shut down the company’s open or semi-open hardware experiments, including the Pippin and Mac clone licensing. From the iMac onwards, Apple doubled down on its now-signature approach: tightly integrating hardware and software to control the entire user experience.

Today, the Pippin occupies a strange space in retro tech culture. While 42,000 units were sold globally, making it rare, it’s not especially valuable. You can find them on eBay for around $600 to $800 — more of a curiosity than a trophy, collected not for its impact, but for the novelty of owning Apple’s forgotten console.