The study of aerodynamics examines how the movement of air on, under, and through a vehicle influences said vehicle’s performance. Be it as a whole vehicle or engineered at the component level (like with a side-view mirror), aerodynamic tweaks can yield dramatic results. As time has gone on, driving dynamics (ie, acceleration, cornering, and even braking), economy, and NVH have all improved significantly with aerodynamic advancements. When you apply the science correctly, beauty, space, speed, and sanctuary come together in a winning formula.

I was reminded of this fact after renting a Chevrolet Malibu earlier this month. The affordable Malibu’s design is elegant, and it’s shockingly relaxing to drive on the highway at modern speed limits in stiff crosswinds. (There was a powerful storm brewing north of my location on Interstate 10 that weekend.)

Chevy’s Malibu proves that aerodynamic benefits are tangible from behind the wheel and pleasing to behold from the parking lot. Of course, this humble sedan is not an outstanding example of aerodynamic innovation, so let’s get to the 10 American vehicles that heavily contributed to aerodynamic progress in the automotive industry.

(Note: Finding accurate metrics like drag coefficients and frontal area for older vehicles is challenging. We did our best to source technical data from automakers while focusing more on the historical impact of their design.)

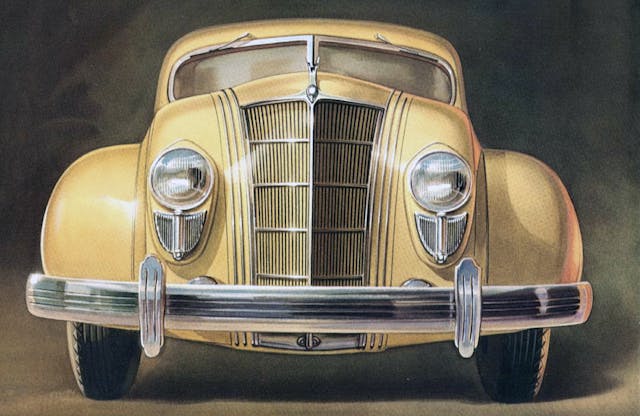

1934 Chrysler Airflow

Walter P. Chrysler once said, “We had the horse and buggy. We had the automobile. Now we have the first real motor car in history.” In hindsight, he was 100% correct in that statement.

Horsepower was on the rise: Chryslers from 1934 had roughly double the 68 horsepower found in a 1924 Chrysler Six. But with the extra thrust came the need for more stability, and making a body that could capitalize on the notion of cheating the wind for better performance was almost the exclusive domain of the 1934 Chrysler Airflow.

The Airflow’s unique shape required a switch to the then-rarely-used unibody design and was formed with input from Chrysler’s own wind tunnel. Sources vary as to the Airflow’s actual drag coefficient (Cd), which is odd, given that drag calculations have been around since at least 1876 and the purpose of the car was to be demonstrably more aero-efficient—you’d think Chrysler would’ve made that number available. Perhaps the car buyer of the era wouldn’t have appreciated such data, and perhaps one day an aerodynamicist with a penchant for history will put an Airflow (or an accurate scale representation of one) in a wind tunnel to determine its drag number. But for now, it’s clear this Chrysler’s streamlined design was “sleeker” than just about any other car in the world in 1934.

1948 Tucker Torpedo

Much like the Airflow, finding and verifying the actual drag coefficient of the Tucker Torpedo has been beyond challenging. The Tucker Corporation wasn’t an establishment automaker, and their problems likely exacerbated the need to use the mathematical formula to calculate the Torpedo’s coefficient of drag. Multiple outlets report the formula netted a 0.27 Cd, but suggested Tucker rounded it up to 0.30.

Facts and figures are hard to market to the general public, and rounding up a figure that significantly would be terrifyingly misguided in our modern times. But the positive reviews of the era didn’t lie, as the Tucker’s streamlined body and fastback roofline were two reasons why it drove so well. The low slung chassis (note how the rocker panels sit below the centerline of both axles!) and aircraft-style wraparound door frames certainly smoothed out the air like a modern car. This is another car that deserves the oxygen of publicity with a trip to a modern wind tunnel.

Chaparral (All)

The innovative Chaparral race cars that bore the fruits of Jim Hall’s engineering labors deserve to be combined into a single mention. They were all given the name of a bird that was more famously known as Road Runners, and their sleek designs did not disappoint. The most notable Chaparrals are likely the 2F (1967) with its innovative spoiler design and the 2J (1970) with “sucker” fans that created a diabolical level of downforce at speed.

While the racing legacy of Chaparrals isn’t as storied as marques like Ferrari, their innovations were game-changing. We lack a verifiable Cd for these race cars, but it’s their advancements in downforce—using air to increase grip and stability—that really mattered. The Chaparrals permanently changed the course of racing, and the principles they took advantage of migrated to street cars. Nowadays, as modified street cars can crank out four-figure outputs with only modest upgrades, downforce engineering has become ever more important.

1969 Dodge Charger Daytona/Plymouth Roadrunner Superbird (Cd 0.29, 0.31)

Chrysler’s “Winged Warriors” reportedly cheated the wind tunnel with 0.31 (Plymouth) and 0.29 (Dodge) drag coefficients. The Dodge cheated the wind better thanks to a sleeker nose, a more upright rear wing, and open ductwork on the fenders to efficiently manage airflow in the front wheel arches.

The motorsport legacy of the Charger Daytona and Superbird are part of a larger battle with Ford’s Torino Talladega and the Mercury Cyclone Spoiler II. This led to the collective Aero Warriors nickname for all four of these homologated race cars. But the two flat-nosed Ford products weren’t nearly as aggressive as Chrysler’s Winged Warriors, and NASCAR closed this aerodynamic loophole before Ford put the similarly slinky Torino King Cobra and the revised Cyclone Spoiler II into production for the 1970 model year. Chrysler easily wins this test with their first-mover advantage!

1984 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am Aero Package (Cd 0.306)

Perhaps it’s surprising that a General Motors product hasn’t been mentioned yet, but the largest automaker in the world put their chips into aerodynamic design in the 1980s. Thinking that a second energy crisis was coming (it ultimately didn’t materialize) and seeing the growing strength of foreign competition, GM invested resources into making some of the most advanced vehicles of the era. And invest they did, with amazing results from vehicles like the third-generation Pontiac Firebird for 1982.

The legendary Gale Banks took a Firebird to 200 mph with twin turbocharging under its low-slung bodywork, but even everyday Firebirds were impossibly low, sleek, and aerodynamic. By 1984, there was an optional aero body kit for the Trans Am, with a smoother front bumper, deeper chin spoiler, and wind-cheating ground effects. This option also came with the plastic wheel covers made iconic by the Knight Rider TV show. While places on the internet suggest these T/As have (an entirely believable) Cd of 0.29, Pontiac’s 1984 sales brochure insists the Aero Trans Am was “only” good for a Cd of 0.306. That’s still no joke for a car designed in the Atari 2600 era of computing.

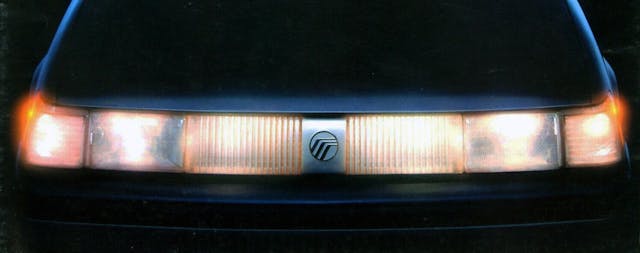

1986 Ford Taurus / Mercury Sable (Cd 0.32)

While cars like the Trans Am introduced aerodynamics to enthusiasts, nobody hit the American heartland like Ford with the original Taurus and Sable. Despite my recollections (as a self-proclaimed Lincoln-Mercury fanboi) that the 1986 Sable’s unique bodywork was more aerodynamic than its Ford Taurus stablemate, literature of the day suggests both revolutionary sedans sported a low Cd of 0.32.

That’s despite the posh Sable having a longer rear deck, a unique C-pillar with full glazing, and quarter panels with integral fender skirts. No matter the differences, the Taurus was a practical alternative to a pricey European sport sedans, while the “sleeker” Sable implemented a light bar to look even more radical than its sibling.

There was chatter that Japanese designers really took a shine to the Sable’s light bar and extra side glass. Perhaps the 1991 Subaru SVX’s full width (non-functional) lighting pods and radical quarter windows were justified by Mercury’s once-radical family car. No matter their global impact, these twins forever changed how we looked at aerodynamics in America.

1988 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme (Cd 0.297)

While the story of the GM-10 family of sedans and coupes was ultimately one of tragedy, the seven billion dollars spent on this platform spawned a series of delights: quad bucket seats, quirky modernist applications of computers, and even a glove block lock that was a combination (and not a key). Subsequent designs of the GM-10 were commonly referred to as W-bodies, and the try-harder componentry seemed to disappear with that name change.

But we are here to discuss aerodynamics, and the 1988 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme coupe wowed us all with a Cd of 0.297. The slender headlights lowered the front end compared to the older Taurus, the door handles tucked into the B-pillar, and the roofline was even more elegant than the 1986 Sable before it. Bottom line, if you appreciate the advancement of the automobile over time, this Oldsmobile always needs to be in the back of your mind.

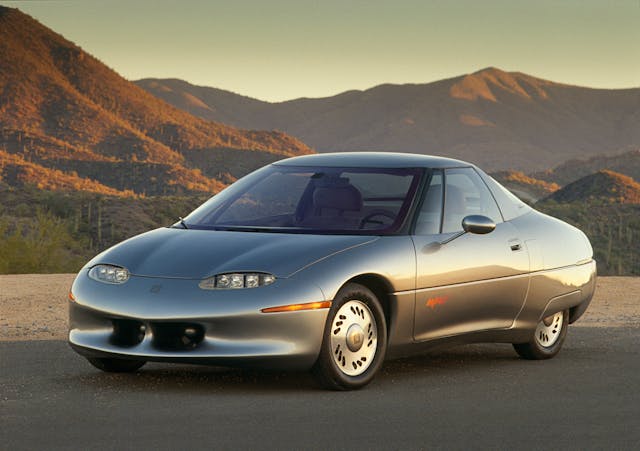

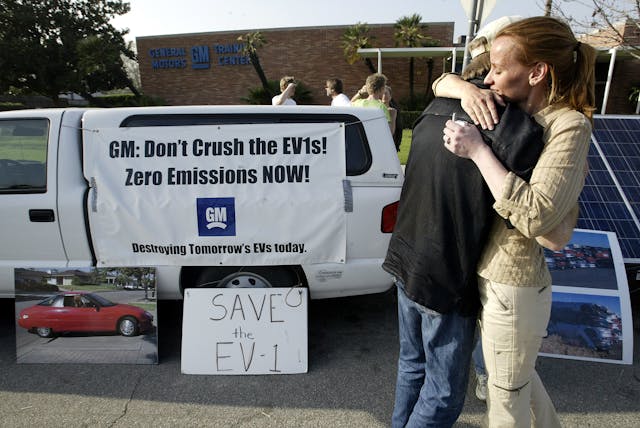

1996 GM EV1 (Cd 0.195)

There are aerodynamic production cars, and then there’s the GM EV1. With a Cd of 0.195, it is only bested by the Volkswagen XL-1: a vehicle that was many times more expensive and had a far less useable trunk. While today’s EVs certainly offer more performance and practicality, the slick coachwork ensured a 60-mile range even with the EV1’s antiquated lead-acid batteries. When GM upgraded the EV1 to nickel–metal hydride (NiMH) batteries, that slick body helped it go a whopping 160 miles on a single charge.

Love it or leave it, the EV1 was proof that electric vehicles could win over a new type of driver, and its demise was the reason why Tesla was formed just a few years later. That commitment to new technology was appealing to consumers, thanks in part to the impressive feats of aerodynamics that General Motors accomplished with the EV1.

2020 Rivian R1T (Cd 0.30)

The combination of aerodynamics and trucks makes about as much sense as oil mixing with water, as an open bed at the back of a cabin is inherently inefficient. But today’s pickups have many wind-cheating tricks to go with their massive footprints, tall cargo boxes, and powerful engines. You see it in the plastic air dams under the bumper, the slightly lowered front end stance, and the removal of as much ornamentation (mud flaps, raised wheel arches, etc.) as possible.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise that the shockingly capable Rivian R1T has a Cd of only 0.30, seemingly unheard of in a modern truck with gasoline motivation. That number is better than almost every aerodynamic sweetheart of the 1980s. While EV trucks have limited appeal (at least based on their sales), widespread implementation of Rivian’s smaller footprint and sleeker design elements would make modern gasoline trucks more efficient. (I reckon they would also be easier to park, too.)

2022 Lucid Air (Cd 0.197)

Lucid was born in part from Peter Rawlinson’s quest to make the best luxury vehicles, bar none. Those who experienced the Air know his team came pretty darn close to it. The Lucid Air has a 0.197 Cd, which is claimed to be the most aerodynamic production car. I have yet to see an automaker contest that claim, and it comes within spitting distance of the teardrop-shaped GM EV1. (The Lucid Air is a much larger vehicle with bigger tires, so it is probably less aerodynamic overall.)

Lucid’s commitment to engineering excellence in their luxury EV sedans lets America take a technological win in terms of aero supremacy. The styling is a delightful mix of quirky and modern. While the future is hard to predict, one must wonder aloud: can we advance aerodynamics any further from this point?

We most certainly can! I look forward to the day when Hagerty Media makes a list of the vehicles with the smallest frontal area. You know, when automakers decide that’s something we need to worry about.