Whether you’re a parent, educator, you work with kids or just have an interest in the lives of young people, you’ve probably already seen the most talked-about – and genuinely outstanding – TV show of the year so far.

Adolescence on Netflix, co-written by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham, has provoked extensive public debate – not to mention praise in the House of Commons from the Prime Minister – about how to tackle the damage that smartphones and social media can cause to young people’s lives.

I’m the parent of a soon-to-be 13-year-old. Before she started Year 7 last September, everyone told me she had to have a smartphone if she wasn’t going to be socially ostracised.

‘How will she communicate with her friends if she doesn’t have WhatsApp?’ was a common refrain.

My husband and I felt strongly – having read a lot of research – that smartphones and teens are not a good combination.

We discussed our concerns with our daughter, listened to her views about what she wanted and needed from a phone, and agreed on her having a severely limited old phone of mine.

We made the screen grayscale (there’s evidence that the colour on smartphones strongly exacerbates the addiction), restricted access to almost all apps and to the internet. If she needs to access a site, the phone pings us with an approval request.

It’s essentially a brick phone with music, maps and Wordle.

Six months later and – surprise, surprise – we haven’t witnessed a single negative repercussion as a result. If she wants to message her friends, she texts them.

She misses out on nothing by not being on WhatsApp except the wasted hours scrolling through endless group chats.

It turns out plenty of other students at her school also have brick phones, and some have no phone at all.

The tide among parents, it would seem, is already turning.

I hear lots of complaints about kids spending too much time on their phones. I’m not sure why we’re castigating young people for that. We all know how addictive they are, for adults as well as kids, not to mention how potentially dangerous.

When I was young, I’d come home from school and watch children’s TV: content made for children and regulated for children.

Now, by giving young people smartphones and unfettered access to the internet and social media, we’re allowing them free rein through the world’s unregulated content: violence, pornography, extreme views.

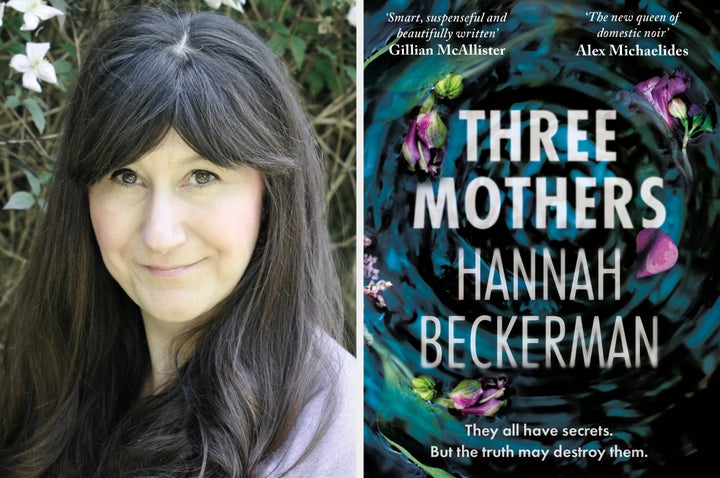

When I started writing my latest novel, Three Mothers – about a 17-year-old girl killed in a hit-and-run and the catalogue of secrets leading up to it – I wanted to tackle teens and their relationship with digital media.

In researching the novel, in which one teen anonymously harasses another online, I talked to a lot of young people about their experiences, and was dismayed how widespread and commonplace toxic behaviours have become.

Girls talked about the range of misogynistic behaviours they encountered: how the same selfie could prompt wildly divergent comments ranging from crude desires from men who want to have sex with them, to accusations that they were sluts.

And as anyone who has seen Adolescence will now know, there is an entire emoji language used by teens on social media regarding the manosphere and incel culture, as well as the deeply misogynistic belief that 80% of women are attracted to only 20% of men, and that therefore the only way most young men can attract women is to trick them into a sexual relationship.

I know that eventually my daughter may want a smartphone. We’ll keep having a dialogue with her and hopefully not have to cross that bridge for a while yet.

But in the meantime, it’s clear that the time for endless debate is over. The Smartphone Free Childhood campaign is doing a sterling job of raising awareness.

Parents need to step up, stop bowing to peer group pressure, and do what’s in the best interests of their children.

Australia has already banned social media for under-16s and a recent poll found two-thirds of young adults in the UK think social media should be banned for under-16s here, too.

Social media companies clearly require urgent regulation. The government needs to stop kowtowing to Big Tech, accept the evidence and legislate.

The wellbeing and development of our young people is at stake: it’s hard to think of a more pressing issue for the PM’s inbox.

Three Mothers by Hannah Beckerman is published by Lake Union Publishing (£8.99)