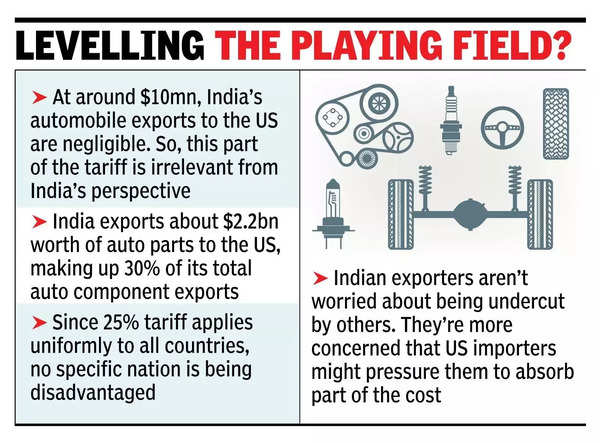

Spoiler alert-the 25% tariff imposed on auto and auto parts is likely to have little negative impact on India. Automobile tariffs would take effect from April 3 and tariffs on auto parts would take effect ”no later than May 3 2025” according to MEMA, Motor Equipment manufacturers Association of USA. Firstly on automobiles, India’s total exports to US at around $10 million, would roughly equate to a rounding error in Japan’s automobile exports to US and is completely insignificant.

On automobile parts, India is a more serious contender with $2.2 billion exports to US, comprising nearly 30% of India’s total automobile component exports. But placed in context, this is under 3% of US’ total automobile parts imports. This is not really what Donald Trump is targeting, but could become collateral damage in his assault on the big exporters of parts to US- Canada, Mexico, China and others.

However, the likelihood of being collateral damage is minimal. The 25% tariff is being applied uniformly to all countries, so every nation’s competitive advantage is impacted equally. Auto parts companies in India do not fear being outpriced by competitors on this account. What they do fear is pressure from importers to absorb at least a part of the cost, thereby eroding profitability significantly. Some companies anticipating this possibility have already started a cost reduction drive.

The other possible threat is local manufacturers in US using this shield of 25% to set up production in US and outprice imports. This is probable against high cost countries like Germany, Japan, Canada etc, that would lose out completely to US manufacturers. However the equation is different in case of low cost countries like India, Vietnam, China and some East European nations. Even with the 25% advantage, US manufacturers would find it challenging to match the prices of components from low cost nations.

The reason is that the cost advantage enjoyed by low cost countries due to labour arbitrage is not in percentages, but in orders of magnitude. As against a worker in auto components paid Rs 30,000 to 40,000 per month in India, a typical US worker would be paid at least $4000/month. This would translate to a 10:1 cost advantage in labour, but the wage advantage is offset by higher productivity in US. This could be anywhere between 2 or 3:1 . This is not because workers in the US work three times as quickly as Indians. Human productivity due to physique is a factor, and machine speed is another but what is significant in the productivity difference is automation. This results in man machine ratios which could be1: 2 or 1:3 in US vs 1:1 in India. Additionally, Indian companies tend to employ larger numbers of indirect labour compared to US where material movement, and other indirect activities also have a larger element of automation. This would extend even to factory staff. Factory management productivity would be higher in the US due to leaner organizations. Indian factory managements typically tend to have more supervisors and middle management. . However even after offsetting the productivity advantage of the US, India would have a labour advantage versus US, the total human costs being anywhere between 300% higher or more.

After this there is the consideration of what percentage of the total cost , the human cost comprises to arrive at the impact on total cost. In this we need to club all three categories-Direct labour, indirect labour and staff salaries. All this put together would normally be at a minimum of 12-15% of the total cost, even in material intensive products . If the total labour cost advantage is 300% , then the total cost advantage would still be 45%. This can be calculated for illustration as- The Indian product would be 85+15, vs the US product’s 85+60, so Indian products have some cushion against US products even after the 25% tariff. This calculation is only for illustration as there are cases where the total human cost is as much as 40%, making it well nigh impossible for local US companies to compete. However if there is a double whammy in terms of very low labour content and abysmally low productivity, then that company could lose out as the OEM’s would expect at least a 10% advantage for importing products versus buying locally. However in most cases the 25% advantage, even clubbed with the 10% cost differential sought by OEM’s can be overcome by Indian companies.

.

Another factor that should make Indian exporters comfortable is that US manufacturers would be wary of setting up capacity to take on Indian products, not knowing how far we can go in dropping prices. This is in addition to the fact that these low cost imports represent a relatively smaller slice of the market. Local manufacturers would first look at the low hanging fruit, ie large volumes of high cost imports from high cost nations.

However, instead of looking at this defensively as to how we can protect our position, the administration should be looking at how this situation can be used as an opportunity to aggressively expand our exports to US, by striking a deal. Why this should be a difficult exercise, given the above cost factors is baffling. Even if the duties on every single manufactured product from USA were reduced to zero, US products cannot outprice Indian products. US products will be bought for value, not price. If the duty on a Harley Davidson for instance is reduced to zero, there is unlikely to be even one buyer of a TVS Apache or Bajaj Pulsar who would switch to a Harley. Similarly, even the lowest model of a Tesla couldn’t compete on price against Indian cars. The same is true for every other product I know of. The tariffs of the Government are not to protect Indian manufacturers, but to make money off the “rich” buyers of these products (“If someone wants a Harley, he will pay twice the price to get it”). Soaking the rich in this context, is outdated thinking of the Nehru era, that has no place today either in economics or as here in geopolitics.

In conclusion, while the 25% tariff poses little threat to Indian auto component makers, it provides an opportunity the Government should seize and capitalize on. The question is whether they will rise to the occasion. From 1947 to 1990 India saw the dark ages until the P.V. Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh Government. They were up against the wall , but used the crisis well to liberalise the economy. India then saw an inflection point. We can hope that the present Government will do the same under compulsion. It should , as it has taken several steps to promote Indian manufacturing in the past. As Winston Churchill (or Rahm Emanuel) said-“Never let a good crisis go to waste”. So Trump’s tariffs could well be good news and another inflection point for the Indian economy.

The author has an IIT-IIM education and has over 20 years’ experience leading auto parts and manufacturing companies in India and abroad